They were all called "George."

Symbols of subservience to white passengers, Pullman Porters helped advance the Great Migration and the Civil Rights Movement, and formed the first African American labor union.

Just before the Civil War, a Chicago businessman named George Pullman started manufacturing Pullman Palace Cars. These luxurious railroad cars had seats that converted to beds at night, with curtains to provide privacy, or in small private rooms. Well-to-do passengers could sleep comfortably during their train travel.

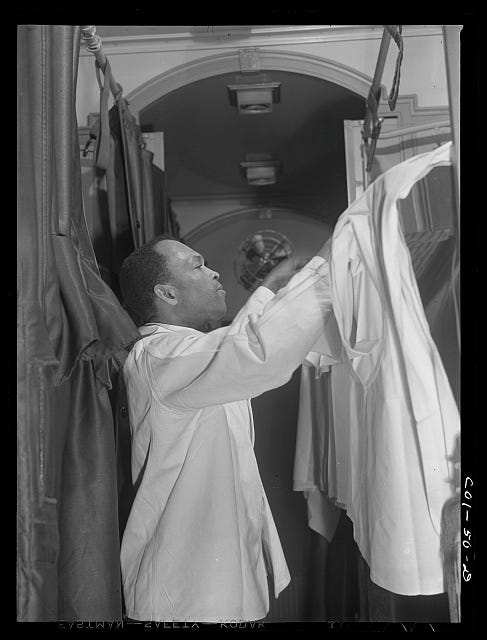

Soon after the Civil War, Pullman began hiring formerly enslaved men to serve as porters on his Palace Cars. Pullman Porters carried luggage and prepared the beds each night. They also cleaned toilets, shined shoes, ironed clothes, and brought the (almost invariably white) passengers food and drinks.

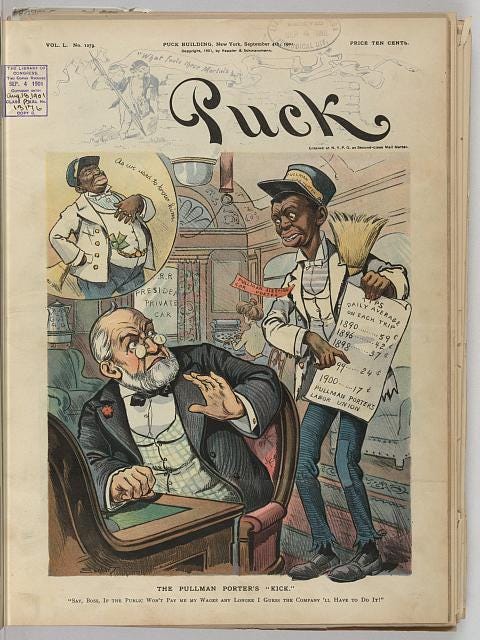

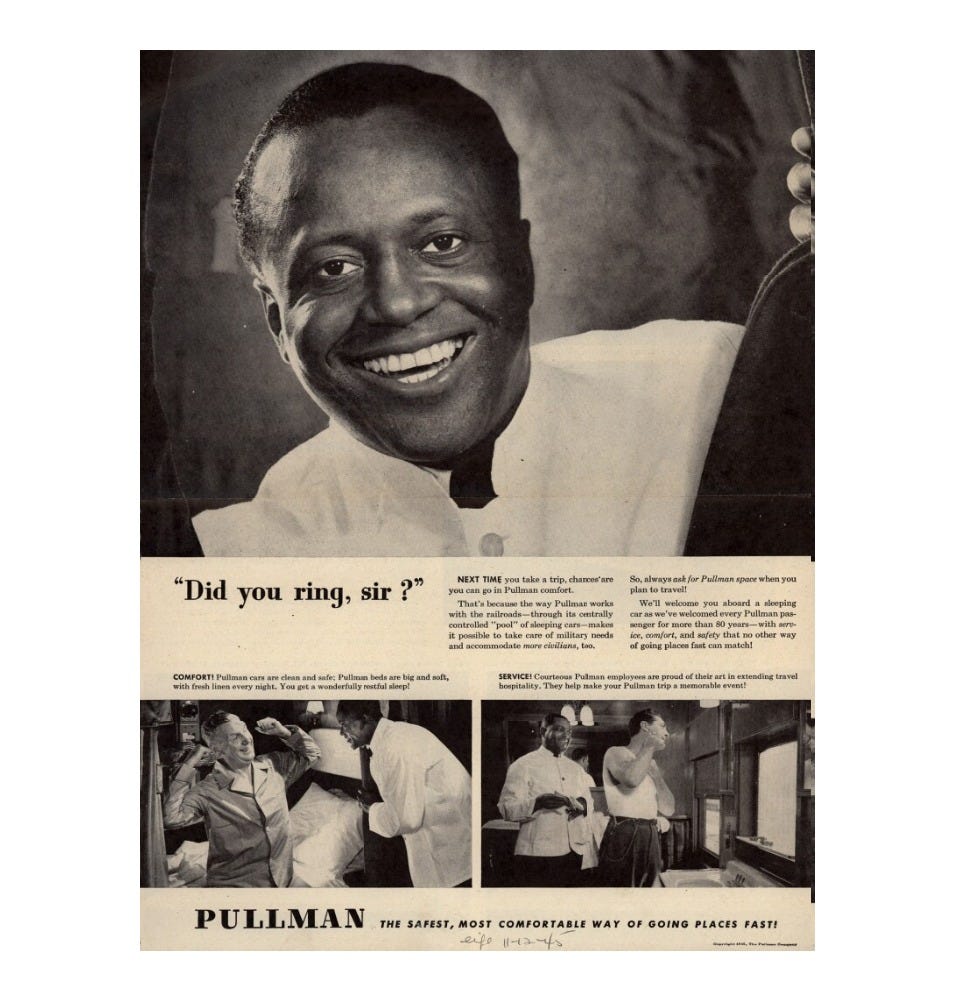

Pullman reasoned that formerly enslaved men and their descendants would be accustomed to waiting on white passengers, catering to their every whim. The porters were paid a wage, but depended on tips for most of their income. That meant that Pullman Porters were appropriately servile, polite, and smiling, even when asked to sing or dance, or perform any number of humiliating tasks.

Pullman cars were not technically segregated because they were owned by the Pullman Company, and leased to the railroad. Nevertheless several states, including Georgia, Texas, and Arkansas imposed separate car laws intended to segregate sleeper cars.

Pullman tickets were much more expensive than those for standard cars, and unaffordable for most African Americans. Black passengers who could afford them were often denied tickets. They were told that there were no more Pullman spots available, even if it wasn’t true. If Black passengers managed to obtain a ticket, they were seated as far from white passengers as possible. In general, the only Black people in Pullman cars were servants and porters.

Pullman porters were usually addressed as “boy” or “George” (after the company’s founder, George Pullman), a holdover from slavery, when enslaved people were called by their enslavers’ names. Porters had to purchase their own uniforms and were required to work at least 400 hours per month. They had to be available to the passengers they served 24 hours a day, sleeping when they had a chance, on the floor or in the baggage car, for a maximum of four hours a night.

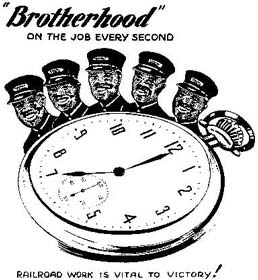

African American railroad workers were not allowed to join the American Railway Union, which welcomed white Pullman employees. So the Pullman Porters formed their own union. The Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters was founded in 1925, with A. Philip Randolph as its president. In 1937, after 12 years of negotiations, the Brotherhood signed a contract with the Pullman company, achieving better pay and working conditions, and cutting their work hours to 240 hours per month. The Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters was the first successful African American labor union.

Aside from their success in the labor arena, the Pullman Porters influenced African American culture, bringing jazz and the blues from the big cities to rural areas, for example. They also smuggled copies of The Chicago Defender, The Baltimore Afro-American, New York Age, New York Amsterdam News, and The Pittsburgh Courier to the South, dropping bundles of the African American newspapers at prearranged spots for distribution and leaving copies in barber shops and churches. In addition to news of interest to African Americans, the newspapers detailed opportunities for better employment, better pay, and a better life in the North. This information was a driving factor for the Great Migration, as six million African Americans moved from the rural South to cities in the North, Midwest, and West.

The work of the Pullman Porters extended beyond trains. Many members of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters went on to be major influencers in the Civil Rights Movement.

A. Philip Randolph, the first president of the BSCP, was the force behind the March on Washington Movement, which pressured Franklin D. Roosevelt to issue an executive order desegregating the defense industry in 1941. Then, with Bayard Rustin as his Deputy, Randolph was the Director of the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs And Freedom.

E.D. Nixon was a Pullman Porter from 1923 to 1946. He was president of the Montgomery, Alabama branch of the BSCP for many years. In 1955, when Rosa Parks was arrested for refusing to give up her seat on a Montgomery bus, Nixon bailed her out and—together with Ralph Abernathy, Bayard Rustin, and a young minister named Martin Luther King, Jr—organized the Montgomery Bus Boycott.

When George Pullman hired formerly enslaved Black men as Pullman Porters, he believed that they would work long hours at hard labor for little pay. He preferred to hire men with darker skin, to emphasize their subservient status and separateness from white passengers. Because the Porters relied on tips for a living wage, they endured racist humiliation and abuse from passengers—with a smile.

Pullman died in 1897. He was succeeded as president of the company by Robert Todd Lincoln, the son of Abraham Lincoln. Robert Lincoln was just as determined as Pullman to limit the wages and opportunities for Pullman Porters. The porters had a saying, “Lincoln freed the slaves and his son re-enslaved them.”

But as the Twentieth Century progressed, the Pullman Porters began to see that they did have the power to make things better—for themselves, for their children, and for African Americans across the United States.

Thank you, this was well written and educational. Thank you for providing Seeds of Justice to us!