Pauli Murray and Spottswood Robinson

A law school paper, a friendly wager, and a landmark Supreme Court decision

On Easter weekend of 1940, Anna Pauline “Pauli” Murray and Adelene “Mac” McBean were arrested in Petersburg, Virginia for violating segregation laws on a bus. After three days in jail, where they practiced nonviolent resistance, they lost their legal case. The following year, Murray applied to Howard University School of Law. She* was accepted. It was at Howard Law that she met Spottswood William Robinson III.

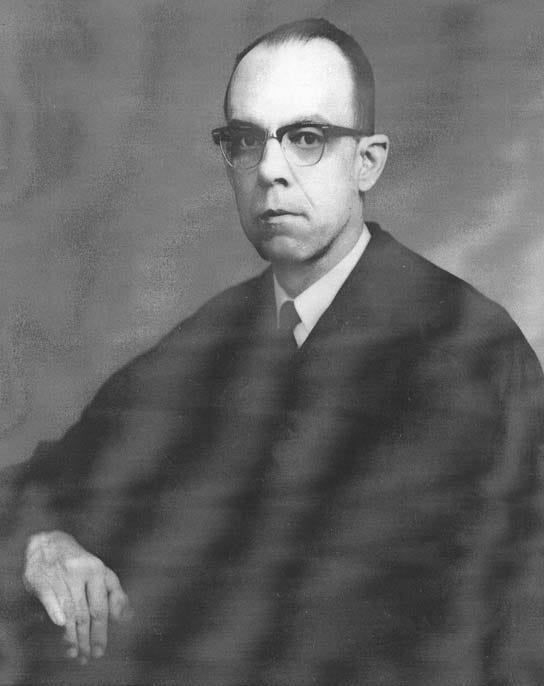

Spottswood Robinson graduated first in his class at Howard Law in 1939, with the highest grade point average in the school’s history. He then joined the faculty there.

In her third year at Howard Law, Pauli Murray enrolled in Robinson’s notoriously difficult “Bills and Notes” class. In the previous year, Robinson had failed nine of the fifteen students in the class. Murray found herself in a two-person study group with Billy Jones. Jones had fallen ill and lost his vision, so Murray taught herself the class material, then taught it to Jones. The highest grade for the class was a 70, with the exception of two students.

Billy Jones achieved an 85.

Pauli Murray earned a 95.

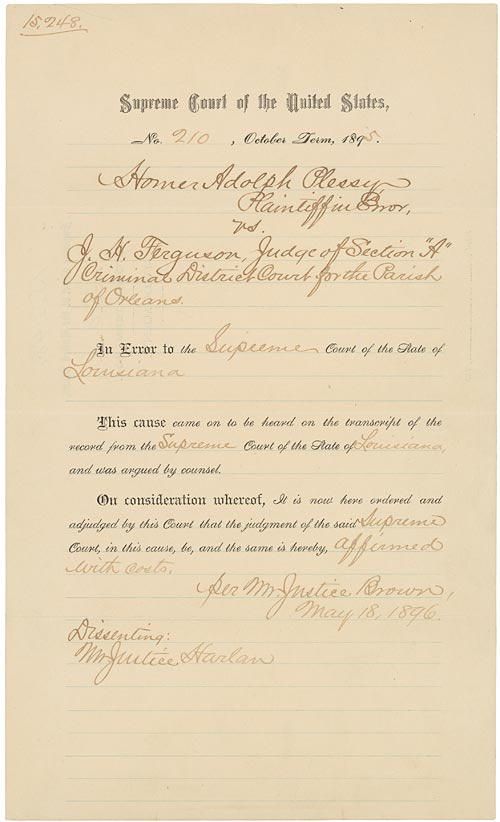

Murray’s final law school paper was titled “Should the Civil Rights Cases and Plessy v. Ferguson be Overruled?” Plessy v. Ferguson was the 1896 segregation case that established the doctrine of “Separate but Equal,” in what is considered to be one of the worst decisions ever handed down by the US Supreme Court.

Attempts to challenge Plessy had centered on the Equal part, arguing that conditions in segregated accommodations were not equal. Indeed, in trains, buses, schools, and many other areas, separate conditions were obviously unequal. In other words, the strategy for challenging Plessy at the time was to make make Separate more Equal. Murry made a different argument, challenging segregation itself, the Separate part.

Murray argued that segregation did indeed stamp Black people with a “badge of inferiority.” The rights to freedom of movement and equal access to public accommodations should not be infringed based on race. Black people had the right to be accepted as equals and the right to die knowing that their children would have the same opportunities. “Only by complete abolition of all laws and customs designed to enslave the Negro, to force him into an inferior category, to restrict his movements and his privileges as a human being endowed with inalienable rights could the institution of slavery be destroyed,” she wrote.

Murray’s male classmates laughed at her idea, but she stood firm. She even bet Robinson ten dollars that Plessy would be overturned within 25 years. Robinson accepted the wager.

Murray graduated from Howard Law in 1944. She was first in her class, and the only woman. In 1950 Murray compiled an exhaustive 746-page book documenting segregation laws in all 48 states and the District of Columbia. States’ Laws on Race and Color included the full text of each state law and local ordinance, often with notes about its history and level of enforcement.

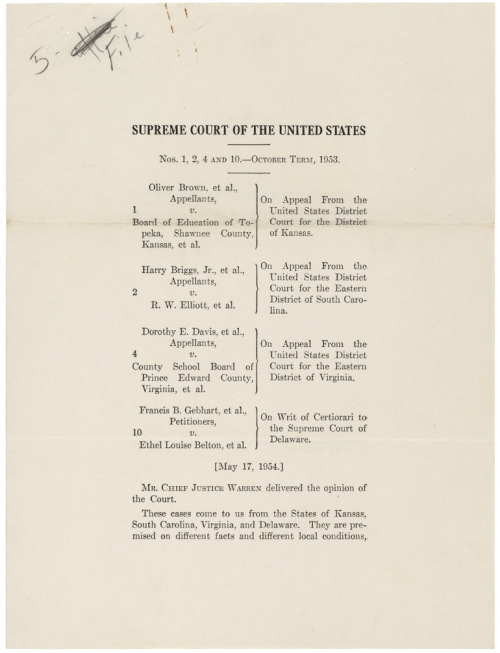

Robinson left Howard Law in 1948. While in private practice in Virginia, he worked for the NAACP Legal Defense Fund, litigating civil rights cases. He was on the team—led by future Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall—that brought Brown v. Board of Education to the Supreme Court of the United States. The team argued that segregation was harmful, even if conditions were equal.

On May 17, 1954, in a unanimous decision, the Supreme Court ruled that separation of the races in public schools was unconstitutional. Plessy v. Ferguson was overruled. Separate but Equal was no longer the law of the land.

“Segregation of white and colored children in public schools has a detrimental effect upon the colored children. The impact is greater when it has the sanction of the law, for the policy of separating the races is usually interpreted as denoting the inferiority of the negro group. A sense of inferiority affects the motivation of a child to learn . . . We conclude that, in the field of public education, the doctrine of "separate but equal" has no place. Separate educational facilities are inherently unequal.”

In 1963, Robinson was back at Howard Law School, this time as Dean. Murray visited Howard and met with Robinson. She asked him what had become of her law school paper. Robinson walked over to his files and pulled out a copy of “Should the Civil Rights Cases and Plessy v. Ferguson be Overruled?” The NAACP team had used the paper in developing their arguments in Brown v. Board. They had also used States’ Laws on Race and Color, which Thurgood Marshall called “the bible” of Brown v. Board.

With the help of Pauli Murray, Plessy v. Ferguson was overruled in only ten years, not the 25 she had predicted.

Murray had won the bet.

Spottswood Robinson paid her ten dollars.

*Pauli Murray was gender nonconforming at a time when gender was strictly binary. In private, she considered herself to be male. In public, and in her writings, she presented as female. She fought for equal rights for women her whole life, even coining the term “Jane Crow” to refer to gender-based discrimination. Historians disagree on the correct pronouns to use. I am using female pronouns to align with her public persona.

Great article!!!