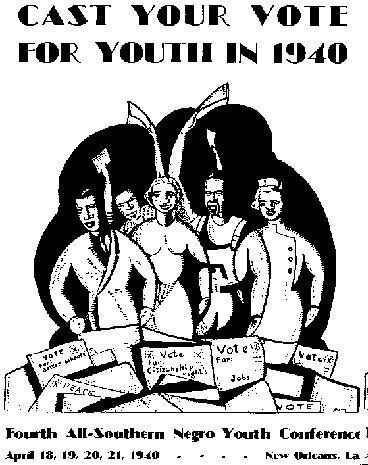

On February 13, 1937, 534 young activists met in Richmond, Virginia at the first Conference of the Southern Negro Youth Congress (SNYC). For the next 12 years, young men and women worked throughout the South, educating and advocating.

The four main areas of focus of SNYC were citizenship, education, jobs, and health. They helped unionize workers, registered voters, and educated people about Black history. The group also promoted the arts through art shows, poetry contests, theater productions, and publications such as Cavalcade, The March of Southern Youth.

And puppets.

The Caravan Puppeteers, founded in 1940 by Waring Cuney, Ramona Lowe, and Peter Price, traveled through the rural South, performing skits with puppets, including “Snottypus” and “Pig.” The group performed indoors and outdoors, sometimes using the roof of their car as the puppets’ stage. Ostensibly, they were there to educate their audiences about such “safe” subjects as farming practices and dental hygiene. But when there were no white people within earshot, the subjects pivoted to “less safe” subjects, like poll taxes, lynching, and sharecropping. The Puppeteers distributed flyers promoting voter registration and SNYC membership.

The Puppeteers were observers as well as performers. They noted, for example, that most African American farmers lived more than 20 miles from schools, too far to walk. SNYC then worked with Black colleges to provide books to marginalized communities.

In another case, a woman asked the Puppeteers for help. Her teenaged daughter, Nora Wilson had been sentenced to eight months in jail for swearing at her white employer after the employer accused Nora’s 11-year-old sister of stealing six ears of corn. SNYC publicized the case, hired a lawyer, and lobbied the Alabama governor. Public scrutiny caused the charges to be dropped and Nora Wilson was released.

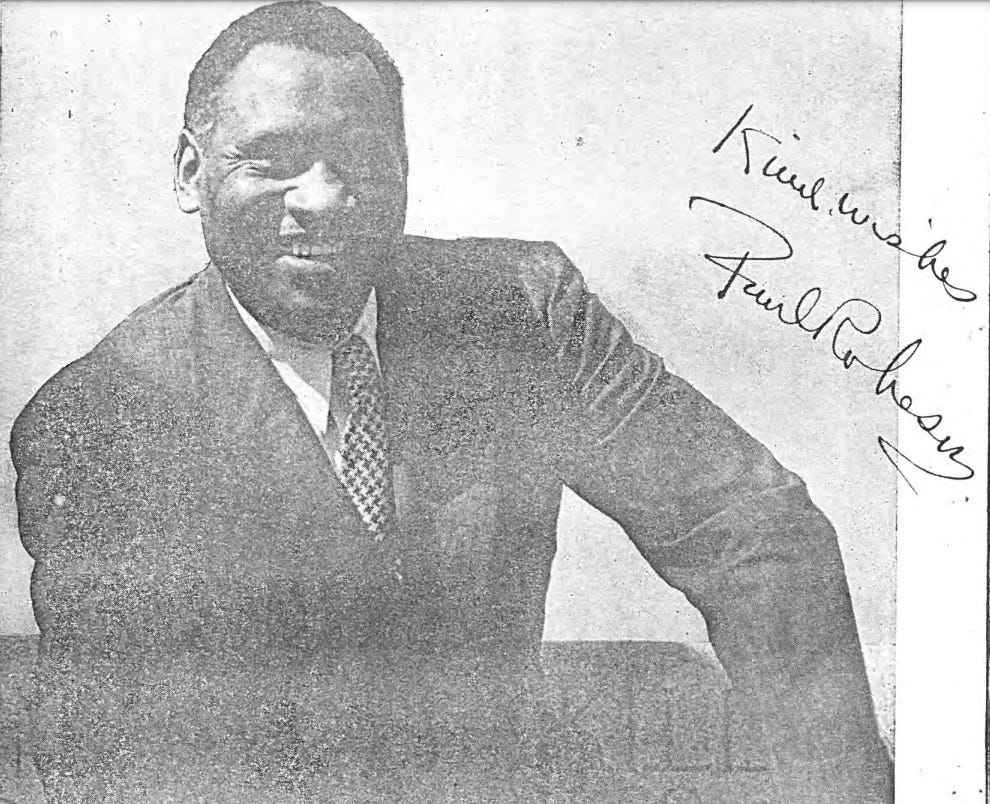

By the mid-1940s, SNYC had become a large, interracial movement with a peak membership of 11,000. The 1946 conference in Columbia, South Carolina attracted over 7,000 attendees and featured singer, actor, and activist Paul Robeson. W.E.B. Du Bois, then 78 years old, gave the keynote address, “Behold the Land.”

As the Cold War followed World War II, and anticommunist sentiments rose, SNYC began its decline. Many SNYC members were also members of the Communist Party. This is not surprising, since the Communist Party was very active in the fight for civil rights throughout the 1930s. In fact, Bayard Rustin was a youth organizer for the Young Communist League in the 1930s, promoting economic justice, civil rights, and desegregation. Rustin quit the YCL when the organization pivoted from equal rights to support of the Soviet Union, but Rustin’s membership earned him surveillance by the FBI.

SNYC also attracted the attention of the FBI and was listed as a “subversive organization” in 1948. Shortly after Harry Truman was reelected, the last SNYC office closed. Esther Cooper Jackson was a member of both SNYC and the Communist Party. “I think SNYC would have continued in the South despite the racism and segregation,” she said, “if the national terror of McCarthyism had not been unleashed.”

Red-baiting and McCarthyism meant the end of SNYC. Although this little-remembered organization ended, the work continued. In the decades that followed, SNYC’s members and supporters, including Mary McLeod Bethune, A. Philip Randolph, Marian Anderson, Pete Seeger, and many nameless others continued the work they began. Even the puppets.